Field Report for Liberal Arts Student Award for Research on Sustainability (LASARS)

By Chiamaka Mangut, graduate student in the Department of Anthropology

Introduction

The present report showcases the results of a pilot archaeological field survey conducted for my Ph.D. dissertation, which focuses on archaeological field research. The study site, known to the local community as Dutsen Kura, is situated on the Jos Plateau in Central Nigeria and is of great significance due to its hilltop location.

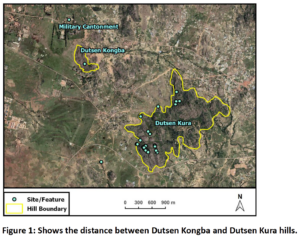

Originally, I had planned to investigate the adaptive strategies of past inhabitants of Dutsen Kongba, another hilltop site located 2 km from Dutsen Kura. However, my request to access the Dutsen Kongba site, which is located within a military premise, was denied. As such I turned my attention to another hilltop site in the same area to answer the same questions set out in my original proposal. Specifically, this research aims to address the following question using archaeological and palaeoclimatic datasets acquired during the excavation of the Dutsen Kura rock shelter:

First, when did local climate/ environmental fluctuations occur, and did this shift influence the technology, which also affected the subsistence strategy of Bace’s ancestors? To better understand the subsistence of the past population, it is essential to understand their technology. Secondly, did local climatic fluctuations influence the dietary patterns of the past population? This would show how the past population responded to climatic fluctuations and ensured food security in adverse climatic conditions. It will also determine whether their diet was adjusted to accommodate plant resources present in the environment because of the shifts in climate or if the dietary change resulted from human agency. To understand this region’s climatic and cultural dynamics in relation to other African regions, I will construct a site chronology using charcoal samples from the excavation levels via Accelerated Mass Spectrometry (AMS).

A brief history of this region

The Jos Plateau region of Nigeria contains some of the most significant Later Stone Age (LSA) sites in West Africa. This region provides evidence of the earliest LSA occupation (ca. 13,000 years ago) (Shaws & Daniels, 1984), though recent evidence suggests an earlier date. The LSA period is of immense importance in West African archaeology, as it reveals the cultural transition and socio-political complexity of the past inhabitants. This period is also the most well-documented and preserved stone age period, the material remains are in situ (Orijemie, 2018), with extensive evidence of cultural transition from mobile to sedentary lifestyles.

Dutsen Kongba, a LSA rockshelter in the Bassa Local Government Area of the Jos Plateau, was excavated in 1973 by Richard York. The site, located 11.5 km west of Jos city, produced a large quantity of lithic materials, with several radiocarbon dates suggesting human occupation around 8,000 bp. While the absence of hearths and other domestic materials implies that the rock shelter was not a residential site, it is plausible that it was intermittently utilized as one. York identified Dutsen Kongba as a stone tool workshop and ritual site utilized by a nomadic hunting community that occasionally inhabited it as a residential site. The rock shelter provides evidence of a clear transition from LSA to sedentism, as evidenced by the shift from microliths to pottery and ground stone materials (York, 1978). LSA populations are known to be mobile, with this in mind and, it was assumed they would have settled on some hills around the vicinity and walked to Dutsen Kongba for their activities as suggested by York. Considering the proximity between both hills, the possibility of residing on Dutsen Kura hill is quite likely.

Methodology

For this research project, we employed a multi-faceted approach, which included systematic surveys, oral history collection, and interviews. In the course of our surveys, we explored the area surrounding Dutsen Kongba in search of another hill with close proximity. Our assumption was that since the excavated rock shelter was suggested to be a workshop and LSA populations were known to be mobile, the populations that worked at Dutsen Kongba hill likely settled close to the hill for easy navigation to and from the workshop site to their residential sites, as suggested by York. After some exploration, we came across a hill just 2 km southeast of Dutsen Kongba hill. We then made inquiries about gaining permission to access the hill, and we were directed to the district head’s residence.

Oral history

During our visit with the community elders, we endeavored to gain a deeper understanding of the newly identified hill, Dutsen Kura. After introducing my research and ensuring local community interest in the subject, we inquired whether community leaders and members had any particular questions they wished to have addressed. They requested a map of the land showing their boundaries and their neighboring villages. Work on this map is in progress and will be presented to the community leaders for edits before final production.

As a result of our conversations, we learned that the Bace people, who reside at the base of the hill and are commonly known as Rukuba by their neighbors, consist of four districts: Mafara, Kakkek, Buhit, and Kishika. Oral history passed down through generations revealed that two of these districts, Kakkek and Buhit, left the original settlement in Upra, Mafara district, where they were all once settled and resettled in Igbak where they occupied the vast land within which Kita Kongba (Dutsen Kongba) and Kita Kobo (Dutsen Kura) are located. The exact date of their settlement in the area remains unclear, but the elders mentioned that there is a link between the past inhabitants of Dutsen Kongba and Dutsen Kura, and that their ancestors ultimately descended from the hilltop to settle at its base.

According to the elders, rituals for rain were often performed at Dutsen Kongba hill when crops needed moisture. Additionally, circumcision ceremonies were also conducted on the hilltop, which is a common practice in some regions of the Jos Plateau. The elders further explained that title holders were often buried on Dutsen Kongba hill as a sign of respect and reverence.

Archaeological Survey

We conducted a preliminary investigation of Dutsen Kura hill in order to determine a suitable location for excavation. Our team thoroughly surveyed and documented the various archaeological features present on the hill. To assist us in this task, we relied on both oral tradition and the expertise of a local youth who is intimately familiar with the area. As the son of the district head of Kakeek, one of the four districts of the Bace, and the leader of the district’s vigilante group, he was able to guide us through the challenging terrain of Dutsen Kura. Due to the steep incline and dense vegetation covering the hill, our reconnaissance was made even more difficult by the rainy season, which made movement up and around the hill a challenging task. We had to use machetes to cut through trees and thick vegetation in order to navigate some sections of the hill.

Features identified on Dutsen Kura Hill

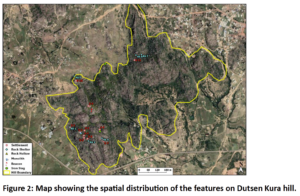

After conducting a detailed exploration of the Dutsen Kura hill and speaking with the community

elders, we were able to identify several significant archaeological features on the hilltop (Table 1). These features include rock hollows, which were likely used for milling herbs and processing cereals, as well as circular rock formations that we identified as house foundations. These patterns of circular bases have been observed in various hilltop settlements throughout the central region of Nigeria and other parts of the country and have been found to date back to the Late Stone Age and Iron Age.

We also identified clusters of circular hut bases that were made of granitic cobbles, and which were arranged in a way that suggested the presence of settlements. These clusters were distributed throughout the hill and were well-preserved, with some of the circular bases being particularly distinctive.

It is worth noting that most hilltop settlements in Nigeria are considered to be refuge sites built during periods of local conflict, and this may also be the case with Dutsen Kura. Nonetheless, the community elders informed us that their ancestors visited the nearby Dutsen Kongba hill for rain rituals and other ceremonies, and that some of their title holders were buried on the hill. This suggests a deep connection between the local community and the hill, and further underscores the importance of our archaeological research on this site.

Table 1: features identified and mapped on Dutsen Kura hilltop

| Features | Number/ present-absent |

| Settlement | 11 |

| Rockshelter | 7 |

| Circular base foundation | 131 |

| Pottery and iron slag surface scatter | Present |

| Rock hollows | Present |

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the features we identified and mapped at Dutsen Kura hill. The hill is significantly larger than Dutsen Kongba, standing at an elevation of 1300 meters above sea level, and measuring 2.3 kilometers in length and 1.2 kilometers in width. During our reconnaissance, we were able to explore roughly one-third of the hill before being forced to halt due to hazardous weather conditions. Despite this setback, our investigation yielded compelling evidence suggesting that the hilltop was previously inhabited.

Interview

To address the issue of sustainability in food production, we carried out a series of interviews with members of the community, including both semi-structured and free-flow interviews. Our focus was on crop cultivation, and we asked a set of predetermined questions to both elders and other members of the community. Below is a list of questions asked.

- What crops did the Bace cultivate?

- Why those crops

- Are there rituals associated with some of these crops.

- Land use management what are the conscious efforts made by the people to conserve the environment.

- What changes in crop production and crop yield have they experienced in the recent past?

- What reasons do they assign to these changes?

- What crops did they grow up seeing and utilizing but has been abandoned now, and why (disease outbreak, no longer time and cost effective)

- Understanding their perception of climate change? (How do they perceive rainfall and temperature)

- What changes have they observed in the climate (rainfall, aridity)

- When did they start observing these changes (did their forefathers complain of these changes)

- How have these changes affected the use of certain plants and availability of resources and what to farm

- How has the effect of climate change affected their diet breadth (choice of food)

- Have they ever had a forecast of an impending climate shift (predictability)

- How did they respond to climate variability (Adaptation strategy)

- How would they have responded better or effectively (risk management)?

- If they have witnessed fluctuating climate how frequent is it in the recent past

Our interview included focus groups and individual interviews to gather insights on the usage of traditional crops and land management practices. Our findings indicate that traditional crops such as Sesamum indicum and Plectranthus esculentus which they identify as Ridi and Risga respectively and Black Beans are being gradually abandoned due to the significant time and energy investment required for cultivation and food preparation, which does not align with the yield output and labor input required. As a result, many indigenous foods are becoming less time and labor effective compared to more modern crops. Another great example is cultivating like millet versus rice.

During our interviews, we had the opportunity to speak with a woman in her sixties who is also a member of the community, who provided a unique perspective on the abandonment of indigenous crops. She cited modernization as a contributing factor, explaining that younger generations no longer view these foods as fashionable and prefer more modern options such as noodles and rice. This has led to a lack of interest in consuming these traditional foods, resulting in wasted resources when prepared.

Considering the role women in food preparation in the community, we believe that further interviews with women will provide additional insights into the reasons for the decline in cultivation of indigenous crops and whether they agree with modernization as a significant factor and how in-depth has cultural interference affected their staple food and other traditional sustainable practices.

Conclusion

The report presents the findings from the 2022 field season, which focused on identifying and mapping archaeological features as a crucial first step in setting the stage for further research. This step is essential to identify a suitable site for excavation with the potential to yield valuable archaeological and archaeobotanical materials.

In addition to the technical research goals, this phase of the project also prioritizes building a trusting relationship with the host community. Many Indigenous communities have legitimate concerns about welcoming researchers to their lands due to past experiences of extractivism and exploitation. Therefore, establishing trust with the community is a fundamental aspect of the research process, and this often requires time and effort. With the support of Sustainability Focused Engagement Award of the Liberal arts, Sustainability Council, I have begun the process trust with my host community and my research team has been warmly received and supported. To further enhance collaboration, I plan to actively involve the community in decision-making regarding the project, seeking their input and incorporating their perspectives as much as possible.

I am grateful to the Sustainability Fund for providing assistance in launching my PhD research, and I am committed to conducting research in a manner that is inclusive, collaborative, and respectful to the host community and their knowledge systems.

References

Orijemie, Emuobosa A. “The Archaeobotany of the Later Stone Age (LSA) in Nigeria: A Review.” Plants and People in the African Past (2018): 362-379.

Shaw, Thurstan, and S. G. H. Daniels. “Excavations at Iwo Eleru, Ondo State, Nigeria.” West African Journal of Archaeology 14 (1984): 1-269.

York, R.N. (1978). Excavations at Dutsen Kongba, Plateau State, Nigeria. In N. David, R.C. Soper and B.W. Andah. West African Journal of Archaeology. 8: 139